Lesson #1:

Getting Ready

The lessons in this toolkit ask some big questions and require some conversations that can get tough. Consider this some pre-work to allow you to set up your practice, your group, and your space in a way that will help your group get the most out of these lessons.

1945 Group of Chinese Women, photograph by Paul Yee, City of Vancouver Archives 2008-010.1698

Personal Reflection

The Suzhou Alley Women’s Mural inherently grapples with notions of power, legacy, and whose story gets told. To dig deep into the mural and what it’s all about, educators and students alike must be ready to have sensitive conversations that potentially could get challenging. It is vital that educators prepare for these lessons by first reflecting on their own positionality.

It can be really challenging to have these sorts of conversations if you or your group don’t feel like you have the right words to articulate your thoughts. It is a great idea to familiarize yourself with some vocabulary before you begin:

- anti-oppression

- colonialism

- decolonial, decolonization

- intergenerational

- intersectionality

- marginalization

- oppression

- patriarchy

- positionality

- privilege

- white supremacy, whiteness

Note: Language and terminology are fluid and complex, especially in these discourses. Learning the definitions for so many terms can seem overwhelming, and you might feel lost when you find conflicting answers. Give yourself permission to sit in this discomfort and let go of the idea that there is one “right” way or solution or that you can ever “master” the topics by learning terminology. This work is a journey, and developing familiarity and comfort with new language is a part of that journey.

Who Are You and What Story do You Bring to the Table?

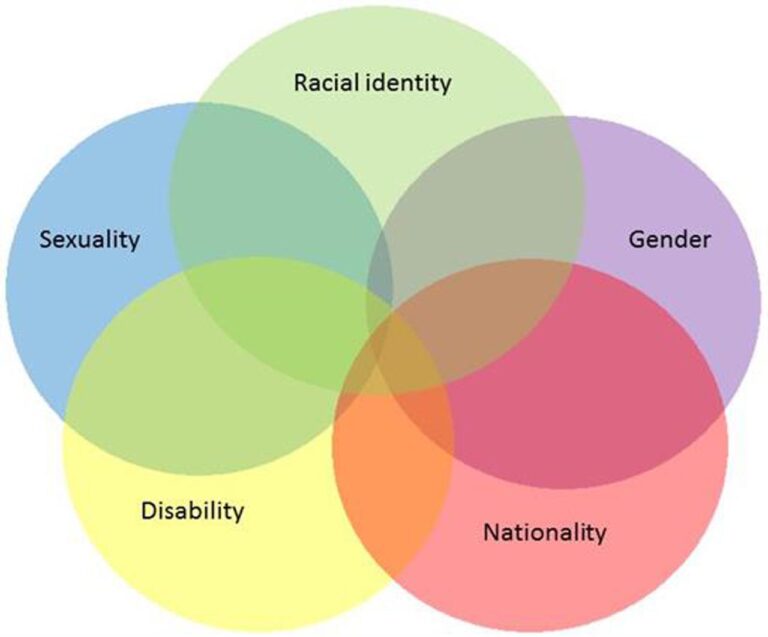

Intersectionality: Law professor and civil rights scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw coined this term to describe how each person’s identities overlap or intersect, and the oppression they experience is a unique result of that intersection. In simple terms, an Asian woman is both Asian and a woman, but because she is an Asian woman, she experiences oppression that Asian men or white women may not.

Intersectionality is a big part of this project. From the start, the intent of the SAWM has been to honour the unsung intergenerational legacies of Chinatown’s women, who, even in the heart of their own cultural community, have remained uncelebrated. This missing visibility is, in large part, due to the intersection of their identities.

Spend some time considering your own positionality. What overlapping circles form your identity? Take a look at Toronto teacher Sylvia Duckworth’s Wheel of Power and Privilege. In what ways do you have power? In what ways are you marginalized?

More importantly: In what ways do you have power that the rest of your group does not? This positionality is vital to remember at all points in your lessons. Be mindful that your positionality will change how you relate to the materials. It will determine how much is at stake for you—and for each of your participants. It will impact how the lessons will look and sound coming from you as the educator and how you will occupy space in the conversation. Consider, as examples:

- Are you a Chinese woman facilitating this material to non-Chinese people?

- Do you have roots, history, and legacy in Chinatown?

- Are you a white settler with multiple generations of family history in BC?

All these scenarios, and countless more, change how a person interacts with the materials. It is important to be aware of and name these biases. The answers to these questions may not come easily and likely will not be simple. When you engage with these questions, what does it bring up for you? What is complicated? What makes you feel defensive or uncertain or validated? Give yourself time and space to sit with everything that this process opens up for you.

By doing so, we can model this reflective process to our group. It is also strongly advised that you hold space for your group participants to engage in a similar reflective process for themselves, so that they can engage with the materials and each other with care, too.

Thinking About the Set Up

Before: Considerations for the Physical Space

The SAWM is deeply rooted in community, and so it follows that the lessons around it should equally practice community care. In most classrooms and gathering spaces, the first step to ensuring such care is to think about the way your space is set up. Is this a space that allows for safe and brave conversations? Is everyone equal in this space? Does it allow for multiple modes of engagement? Consider your space anew by asking questions like:

- How can I arrange desks in the classroom to allow everyone to be seen while in discussion?

- How might I arrange the layout of my classroom so that everyone can easily see all visuals (i.e., projector, whiteboard)?

- How might I create enough space for students to get up and move around in the classroom comfortably when needed?

- Where and how can students find safety if they need a break?

- How can I include principles of pedagogical talking circles?

- situated relatedness

- respectful listening

- reflective witnessing

- reciprocal engagement

During: Crafting Some Community Guidelines

It is a good idea to set up some community guidelines to keep the lessons grounded in respect, care, and safety. There is no right or wrong way to develop a community agreement. Find what works best for your group. Prompts to get your community thinking include:

- What do you need to feel comfortable in this space and in this work?

- How do you best like to contribute? Talking, writing, small group discussions, etc.

- How do we communicate with one another respectfully when something is problematic? What might this look like?What is the best way to ensure that everyone takes up equitable space?

- What might participating equitably look like?

- What are expectations about respect that we can share among everyone in the room—students and teachers alike?

If you are not familiar with the idea of a community agreement, consider looking up examples online. Sometimes, groups need prompts and direction. Most community guidelines take the form of an agreement that everyone can see, revisit, and point to. Though it is the responsibility of the whole group to stay true to the agreement, it is your job as leader to hold everyone to it. That is how you keep participants safe and engaged.

After: Following Up and Continuing the Conversations

One of the gifts of the Suzhou Alley Women’s Mural is that it opens up rich and powerful dialogue. Make sure this dialogue doesn’t end after one session! The following lessons offer many suggestions on how to move forward with this work and support participants, especially young people, who are moved by this project. If you haven’t already, consider taking a field trip to see the mural in person!

Follow up discussion topics:

- How can you and your group carry on the conversations that this mural project has evoked?

- How can the SAWM inspire further good?

- How can your group continue to honour the stories of unsung Chinese women, as well as the countless other people whose stories have been ignored by history?

- What is something that stands out about this mural that you want to continue learning or talking about with others?